DO YOU REMEMBER WHERE YOU WERE the first time you heard a Bowie song? Sitting here today, the day of his death, I can still remember that moment. Like it was yesterday, so many yesterdays ago.

The first time I heard a Bowie song, I was sitting in the passenger seat of a convertible Karmann-Ghia. I was riding with the editor of the high school yearbook, a brown-eyed girl whose name escapes me now. She pushed a cassette tape into the deck and turned it up.

Pushing through the market square,

So many mothers sighing.

News had just come over,

We had five years left to cry in…

”What’s this?” I asked.

She looked at me like I was from another planet. Usually she just looked at me like I was a sophomore. She was a senior so the look was pretty close to the same thing.

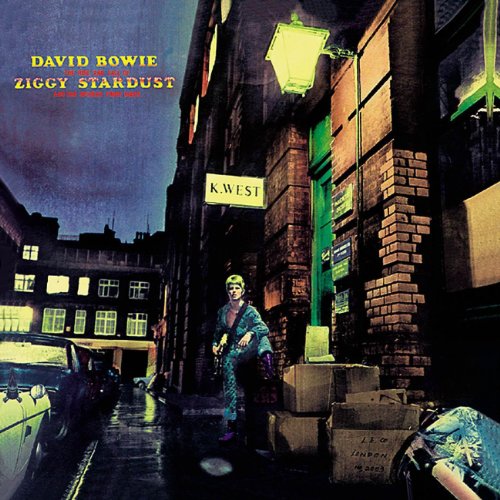

“Ziggy Stardust,” she said. “David Bowie.”

She gripped the wheel tighter and sped down the road, barely making the yellow light. We were in a hurry to get back to her place. Not for the reason every other guy in Jordan High wanted to get back to her place, but because we had run out of rubber cement at the yearbook office. It was a classroom during the day but after 3:30 it became our office. She was the senior editor, in charge of a staff of about a dozen students. I was the illustrator, compositor, and pretty much anything else she felt like bossing me around at. I didn’t mind.

News guy wept and told us:

Earth was really dying.

Cried so much his face was wet,

Then I knew he was not lying…

“You don’t really get this music, do you?” she asked.

I didn’t. But I wasn’t going to tell her that. I didn’t know much about girls but I knew if you didn’t know the answer to their questions it was better to shut up, on the off chance they might mistake you for being “mysterious.”

We drove down Hope Valley Road, past towering pines choked in kudzu. Late spring in North Carolina can bring some hot days, and this was one of them. The back of my shirt stuck to the seat but with the top down and the wind racing by it wasn’t so bad. I heard cicadas buzzing, that Doppler effect as one swarm faded out and another faded in. A kid on a riding mower waved at us. The earthy, syrupy smell of fresh cut grass as we passed by.

I heard telephones, opera house, favorite melodies,

I saw boys, toys electric irons and T.V.’s…

Hope Valley was the upscale suburb where the rich kids lived. I had been there a few times, in baseball games on better ball fields against kids with better uniforms, better gloves, better coaches. They even had real Gatorade, not the powdered stuff the coach of our team—the Parkwood Volunteer Fire Department—gave us. Whenever we beat the Valley kids, which wasn’t often enough, we spat in our hands before the obligatory “good game” handshake line. Then we piled back into the coach’s van and drove out of their manicured paradise, back to our middle-class suburb off Highway 54.

Becca was her name, I think. But I could be mistaken. That ride in the Karmann-Ghia was a long time ago.

My brain hurt like a warehouse,

It had no room to spare.

I had to cram so many things to store

Everything in there…

We passed the Hope Valley Country Club and wound down a couple side streets. She didn’t stop at the stop signs, just slowed down enough to make sure we weren’t about to crash into anyone.

And all the fat-skinny people,

And all the tall-short people,

And all the nobody people,

And all the somebody people…

We took another corner and lurched into her driveway. Her house was easily twice as big as mine. Her yard was smaller though. Not that that was any great thing, having to mow a half-acre full of pine cones—and trying to rake pine needles!—was nothing to brag about. She turned off the engine. Far away, someone was cutting grass, the buzz of the lawnmower round and echoey.

I never thought I’d need so many people…

I figured I would wait in the car. That seemed like the cool thing to do. Unless she invited me in, then I’d act cool about it, like maybe shrug and follow her in. I had been working on this plan for about a mile. It seemed like a good plan.

She cut the engine and the music stopped. She got out of the car and walked to the door. Reached in her purse and got out her key. She had her own key! My mom was usually home so I didn’t need my own key.

“Hey!” Becca shouted, and gave me a what are you waiting for look.

I shrugged my coolest shrug and peeled my back from the seat and walked up the drive. Now that we weren’t moving it was really hot. I wondered if the heat had melted the condom I kept in my wallet “just in case.” My friends and I always kept one “just in case.” But so far there had been no cases. Would this be one?

Oh god, was that what this was about? Of course! It didn’t take two people to go get a jar of rubber cement. Why hadn’t I figured it out before? Why is it so hot today?

She stood at the door humming Five Years. She waited until I was right beside her before inserting the key.

“Don’t touch anything,” she said, and opened the door.

A blast of cold air hit me. They kept their air conditioning on high, all day! A fool and his money, I could hear my dad say, and I shut the door quickly.

“It’s in my room,” she said, motioning down the hall. “Want a coke?”

“Sure,” I said, and she popped off into the kitchen.

I walked down the hall. There were pictures on the walls, same as my house. There in the pictures their family looked pretty much the same as mine. The same shots of Christmas morning, same unrecognizable aunts and uncles. Same yearly family portrait from the mall, same painted-on smiles waiting for the flash to go off. Her parents looked pretty much the same as mine. I guess in two dimensions all parents look pretty much the same.

I got to the door of her room. It was open a bit but I didn’t dare go in. Not until she got there, anyway. I didn’t want to seem like a creep. I shivered, the sweat on my back cold from the air conditioning.

“Here ya go,” she said, handing me a Coke.

In North Carolina every soda was a “coke.” But this was a real Coke, not the store brand. In a bottle, even. That classic bumpy bottle, the ridges cold in my hand.

“Thanks,” I said. “Nice room.”

“Oh brother,” she said and took a swig of hers.

She walked into her room and I followed. Everything was neat inside, her trinkets squared away, her bed made.

“If my boyfriend asks, tell him we weren’t doing anything.”

“So, uh… what are we doing?”

She laughed and pushed me onto the bed. She stood there, looking down at me, Coke in hand. I took a nervous sip.

“What do they say about me?” she asked. “At school?”

The kids said a lot of things. That she was kind of a fox, not the foxiest in our school, but maybe the smartest. Maybe the craziest, too.

“Nothing,” I lied.

“Thanks a lot,” she muttered.

“No, I mean, I don’t know. The usual?”

I sipped at my Coke. The fizz burned on my tongue, the sweet sting of liquid sugar. A drop of cold sweat slid down the bottle and trickled between my fingers. The Coke was the same dark brown as her eyes. I wanted to never leave that room.

She looked at me for a long minute. She hummed the whole time, that same song from the car, Five Years. I sipped my Coke and tried to pretend it was no biggie, crazy foxy chicks were always humming songs to me. Then she went to her closet and opened the door. I could hear her singing:

A girl my age went off her head,

Hit some tiny children…

Maybe she was crazy. Maybe staying in that room wasn’t such a good idea after all.

“I gotta pee,” I said, and walked out.

I found the bathroom, put the Coke on the counter. Splashed some water on my face. Checked my wallet. How long had that condom been in there? Freshman year? I threw it in the garbage. Then I thought of her parents finding it and I fished it out and put it back in my wallet. I flushed the toilet for effect.

When I got out of the bathroom I heard a car horn: beep, then beep beep! I went outside and there she was, back behind the wheel, the engine running. She held up the can of rubber cement. It was time to go. I got in and she turned up the tape. The song was half over.

I think I saw you in an ice-cream parlor,

Drinking milkshakes cold and long…

“He probably won’t ask,” she said as she put the car in reverse and backed out of the driveway.

Smiling and waving and looking so fine,

Don’t think you knew you were in this song…

The Karmann-Ghia raced back through the Carolina heat. Back from her upscale neighborhood, past the country club and gas stations and apartment complexes, back to our school. She pulled into the parking lot and found a spot. She stopped the car but didn’t turn it off.

“You have to listen to the end,” she said.

And it was cold and it rained so I felt like an actor

And I thought of Ma and I wanted to get back there.

Your face, your race, the way that you talk

I kiss you, you’re beautiful, I want you to walk…

“You still don’t understand, do you?” she asked.

I shrugged. I didn’t care if it was the cool thing to do or not. She was someone from another planet, speaking words I couldn’t yet understand.

“This time. For us. All of us. This time, right now…” she said, and turned it up.

We’ve got five years, stuck on my eyes.

Five years, what a surprise.

We’ve got five years, my brain hurts a lot.

Five years, that’s all we’ve got…

We listened to the song until the very end. Five years, five years, five years… it seemed to go on forever. By the time it was over she was crying. Then she dried her eyes and we got out of her car and went back to the classroom to work on the yearbook.

Five years later my life would be different. I transferred from Jordan High to the School of the Arts—the live-in art school like on that show Fame—where I graduated, only to drop out of college. I would go to New York, hang out with the wrong crowd and leave one desperate midnight, on a plane bound for San Francisco. There I would meet another brown-eyed girl, and we would have a daughter together. All in five years.

Five years, what a surprise…

David Bowie called it. Turns out I was in the song after all. And, most likely, so were you. Do you remember?